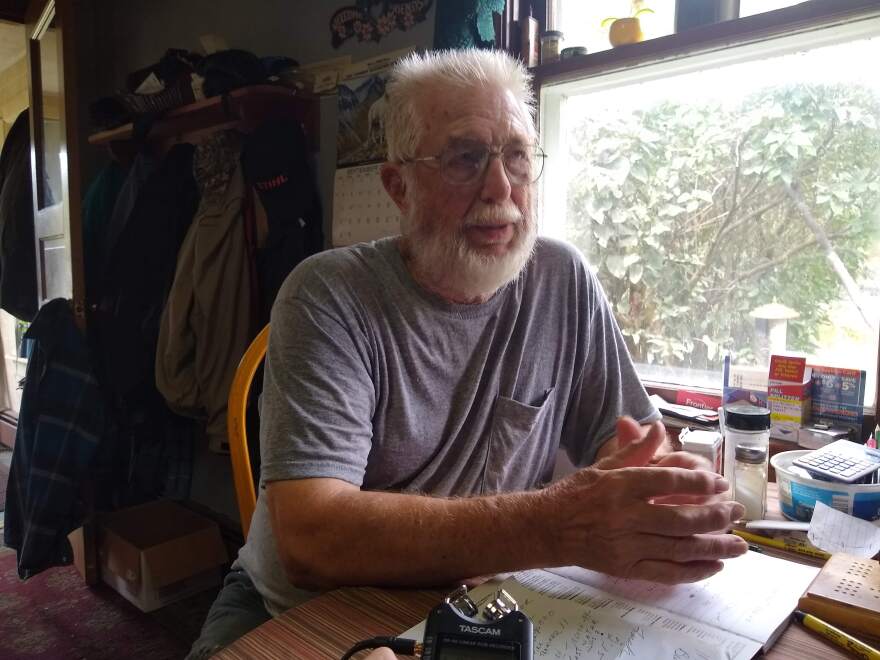

Ron Wiedeman’s ancestors came here around 1900, as best as he can tell.

It’s a swath of land along the Wisconsin River in the Town of Crescent, just southwest of Rhinelander.

“I’ve lived in this area my whole life,” said Wiedeman, sitting at his kitchen table.

When he was a kid, the spring now known as Crescent Spring was on his family’s property.

“Just clean, fresh water, always clean, and good tasting water,” Wiedeman said. “I’ve [drunken] out of there since I was probably eight years old.”

The spring is now along South River Road and open to the public. It’s a popular place to fill water bottles, jugs, and containers.

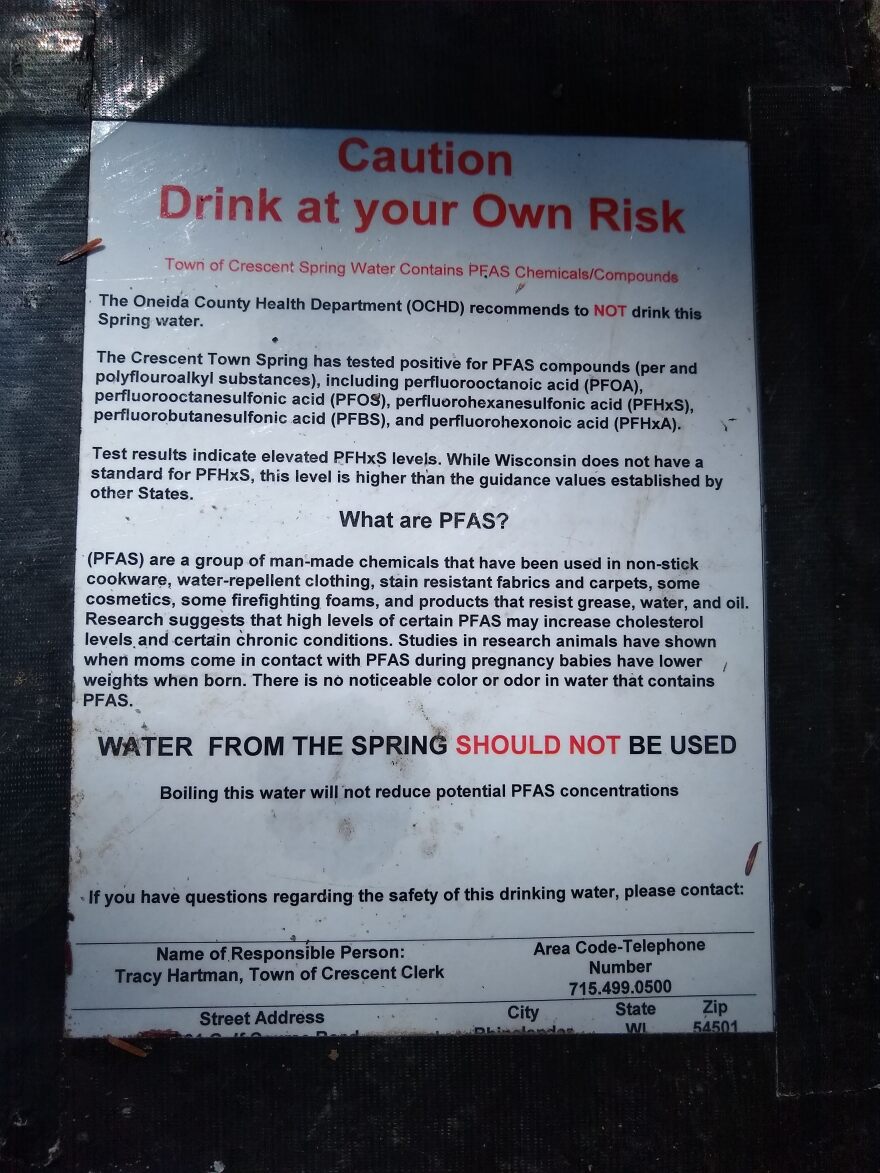

But a month ago, testing found the water had high levels PFHxS, a type of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) drawing attention in Wisconsin and nationwide.

PFAS are a family of manmade chemicals used in carpeting, stain-resistant clothing, food wrappers, and other places. They may be linked to health problems like higher cholesterol, a higher risk of thyroid disease, and reduced female fertility. They’re the same chemicals found this summer in Municipal Well 7, a drinking water source for the City of Rhinelander.

At the Crescent Spring, florescent ribbons and bold “Do Not Drink” signs confront visitors like Crescent Town Clerk Tracy Hartman.

“I hear a lot of, ‘It’s good water, it’s fresh water, we really like it, we know there’s nothing in it,’” Hartman said.

“Obviously, there might be,” she added after a short pause.

Hartman said some people drive here from an hour away to collect the water.

But only a few hundred yards to the south might be an answer to the water quality puzzle.

“It’s still called the Crescent Dump,” Hartman said. “If you say it to residents, some of them will actually know where you’re talking about.”

The dump site is still open to Town of Crescent residents to drop off brush, though it no longer accepts garbage liked it used to do. Even so, two rusted cars, an old basketball hoop, and plastic culverts are visible on the site.

Wiedeman, whose family owned the property before it belonged to the town, remembers watching bears and shooting at rats at the dump.

“Everything went into the dump,” he said. “It’s stuff that probably shouldn’t be in a dump today, but at that time, that was where it went.”

The dump was closed in 1989, according to minutes from Crescent Town Board meetings.

The DNR inspected the site in 2003 and 2007.

“The answer throughout [those inspections] is, no, there’s really nothing else that needed to be done,” Hartman said.

In 2003, DNR inspector Cathy Cleland wrote the site was properly closed, and the nearby spring had always sampled safe. In 2007, Cleland wrote she learned that, in the 1980s, barrels of waste from a bankrupt cleaning business were left there. The DNR picked them up after they started to bulge.

Despite the mostly favorable past inspections, Bart Sexton can’t rule out the old dump as a problem for nearby water, saying “it’s a possibility” the dump contributed to the current contamination.

Sexton is a professional soil scientist at Sand Creek Consultants in Rhinelander. Before that, he served 16 years as the Oneida County Solid Waste Director.

Sexton says leachate, the liquid seepage from landfills, almost always contains PFAS, although water contamination often has several sources.

“It’s difficult, at this point in time, if you have a detect in a well, to say, ‘Oh, okay, we’ve got a single source.’ It’s going to take a little more environmental investigation,” Sexton said.

Sexton is also curious to find out the source, or sources, of contaminants at a nearby well which served even more people.

In June, a test on Rhinelander’s Municipal Well 7, located on the grounds of the Rhinelander-Oneida County Airport, showed elevated levels of the two best-known PFAS compounds, PFOS and PFOA.

The city shut the well down and started drawing water only from its other wells, which tested safe.

But the test got some people thinking.

Well 7 is at the airport, the airport stocks aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), which is used to fight airplane fires, and AFFF is a known source of PFAS.

That foam is kept in white plastic containers next to the airport’s fire truck in the truck’s garage.

“It smothers the fire,” said Airport Director Matthew Leitner, explaining how AFFF works. “It deprives it of oxygen, and then, of course, takes away the source of the flame.”

To comply with rules set by the Federal Aviation Administration, once a year, the fire truck sprays two to four gallons of the foam as a test. Most of it goes into a bucket, then to a disposal tank in the garage. The rest is on the ground.

The airport has never used the foam on an active fire. In mock fire exercises, it uses only water.

“We don’t use [AFFF] regularly. We use it extremely sparingly,” Leitner said. “It’s not something that we play with, and it’s not something that we would ever play with.”

Two to four gallons may seem minimal. But Sexton, the soil scientist, says AFFF discharge still could have caused the contamination in Municipal Well 7 and to Rhinelander’s water supply.

“Absolutely. It’s a potential and that’s all we can say at this point,” Sexton said. “When you start talking parts per trillion, it doesn’t take a whole lot of contaminant to reach that sort of a limit.”

In its ongoing investigation, the DNR sent letters to 19 commercial property owners near the airport, hearing back from 16 of them.

All but three said they didn’t use or store PFAS.

The three included the airport itself, a manufacturer, and a cleaning company.

Manufacturer Lake Shore Systems, said it does not “have sufficient information to provide you with a response.”

Cleaning company K-Tech uses products with PFAS, but doesn’t manufacture it or discharge it on site.

“The information provided helps the [DNR] narrow its investigation into which party(ies) are responsible for the discharge of PFAS into the environment,” wrote DNR Communications Section Chief Andrew Savagian in an email.

The state-recommended PFAS limit, 20 parts per trillion, is a tiny concentration. That’s like 20 drops of water in an Olympic-sized pool.

One of the only places in the state testing for those low levels of PFAS is in a nondescript brick building on Crandon’s main street. Water testing company Northern Lake Service and its president, RT Krueger, own a quarter-million-dollar machine to do it.

“It’s liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy. It’s a neat machine,” Krueger said.

Krueger calls PFAS testing extremely expensive and extremely challenging. The test results regulators want push the outer reaches of current research and technology, he said.

“Coming from somebody that has been involved in this literally since I was a little kid…there is nothing anywhere near as complicated as this one is,” Krueger said.

Krueger is worried research on health effects and testing methods haven’t caught up with the public concern and the thirst for government regulations.

“Once we get to the point of saying, ‘You have this in your water at Level X,’ we just reached the limits of the information that we’re going to hand out,” he said.

Back at his rural home in Crescent, 78-year-old Ron Wiedeman isn’t a chemist.

But he can feel a similar confusion about water quality and the information surrounding it.

“There’s such a question about these PFASes, or whatever you want to call them, that a lot of people don’t understand it,” Wiedeman said.

Wiedeman sees the ribbons and health notices.

But he’s still drinking from the Crescent Spring.

WXPR is preparing a panel discussion on PFAS topics in the coming weeks.

If you have a question you’d like answered, email ben@wxpr.org or submit a question through our Curious North program.

_