On Tuesday, Scott Blado found good news as he dipped scientific instruments below the ice on the Big Eau Pleine Reservoir in Marathon County.

“Right now, we’re seeing [a reading of] 10.9 dissolved oxygen, which is fantastic. We couldn’t ask for anything better than that at this time of the year,” said Blado, an environmental specialist for the Wausau-based Wisconsin Valley Improvement Company (WVIC).

Blado tests multiple points on the reservoir every week, and on Tuesday, he saw a significant jump from the week before.

But getting enough dissolved oxygen, which is critical to aquatic life, can sometimes seem like an ongoing struggle on the 18-mile-long Big Eau Pleine. It has for years, and the associated effects have been striking.

In the summer of 2008, the 7,000-acre reservoir turned the color of neon-green pea soup, a victim of a massive algae bloom. The next spring, thousands of dead fish washed up on shore, victims of depleted oxygen in the water. The bloom caused that depletion of oxygen.

That fish kill sparked local residents and the WVIC into aggressive action. Now, they’re artificially creating acres of open water in the winter to try to improve water quality and help the fishery survive.

Ben Niffenegger, the WVIC Environmental Affairs Manager, filled water sample bottles with Blado on the ice Tuesday.

He explained the issues are due, in part, to the Big Eau Pleine’s differences from Wisconsin River system reservoirs farther north, like the Rainbow, Willow, and Spirit.

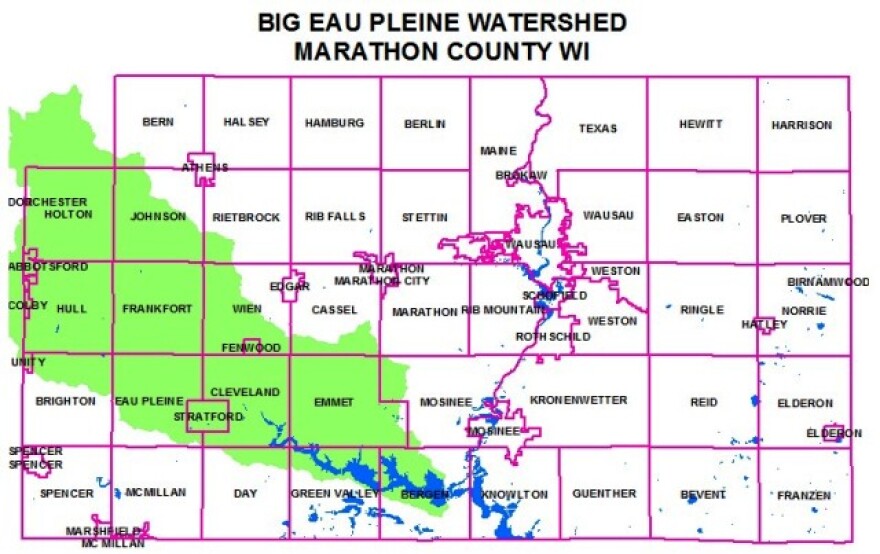

“The watershed is heavily dominated by agricultural uses rather than forested,” Niffenegger said. “The Big Eau Pleine has an agriculturally-dominated watershed.”

The Big Eau Pleine River was once shallow and meandering until it was dammed in 1937, creating the reservoir. About a quarter-million acres of land drain into the water body, much of them farmland with plenty of manure and other phosphorus fertilizers.

“It’s that link of soil and land practices with nutrients and the corresponding impacts, then, on water quality,” Niffenegger said.

The impact?

The Big Eau Pleine has eight times more phosphorus than it should as a healthy flowage.

The domino effect is simple. As phosphorus drains into the reservoir, it touches off algae growth. When algae decomposes, it draws large amounts of oxygen from the water, depleting the oxygen needed for fish and other aquatic life.

It’s worst in winter, when ice cover means oxygen in the air can’t mix into the water.

John Kennedy has become familiar with this process.

He lives 30 miles west of the reservoir near Loyal, but grew up visiting family on the water body with his

father.

“My dad passed in April of 2008, and just kind of left a big void in my life,” Kennedy said.

To help fill that void, Kennedy started fishing again on the Big Eau Pleine in the summer of 2008.

But that same year, the historic algae bloom on the reservoir produced water like he’d never seen.

“This was just pea soup, basically, but almost a neon color, really, really bright,” Kennedy said.

That winter, the decomposing algae sapped oxygen from the reservoir, leaving little for the northern pike, muskies, walleye, and other fish to survive.

“When the ice went out, I went and looked and walked the shore and took some pictures, and it was just terrible,” Kennedy remembered. “It was just fish stacked up, thousands of fish washed up to shore.”

Though he didn’t live on the reservoir, Kennedy got involved with a newly energized BEPCO, the Big Eau Pleine Citizens Organization.

The following winter, along with the WVIC and volunteers, he helped install a new aerator system on the reservoir. Set up about midway through the Big Eau Pleine, the aerator was turned on this winter a few weeks ago.

“It was really the next day where you’d start to see some geysers, almost, shooting up through the ice and through the snow,” said the WVIC’s Jay Dick.

Fourteen long, snaking tubes shoot air into the reservoir, and as the bubbles rise, they break through the ice, eventually creating huge circles of open water.

“It’s not the bubbles in the water that are providing oxygen,” Niffenegger said. “Really, it’s the wind and wave action that circulates oxygen from the air and transfers it into the water.”

The system opens 30 to 60 acres of water on the

reservoir, creating what Niffenegger calls a “limited refuge” for fish.

It’s a partial solution to a problem brought into clear focus by that fish kill more than a decade ago.

“Sometimes it takes a dramatic event like that to really reiterate how serious the water quality issues are in the Big Eau Pleine Reservoir,” Niffenegger said.

Organizations like the WVIC, BEPCO, and a relatively new farmer-led group, the Eau Pleine Partnership for

Integrated Conservation, are encouraging new agricultural strategies to address the root problem: too much phosphorus running off into the water.

The groups suggest taking steps like planting cover crops and cutting back on winter manure spreading.

Once tense, the relationships between those diverse groups continue to improve, said Niffenegger.

“It’s moving in a positive direction, but it’s a slow process,” he said. “We’ve been doing things a certain way for over 100 years in this state.”

If all this work prevents another fish kill on the Big Eau Pleine, John Kennedy will be happy.

It will make it easier to pass down a tradition on the reservoir his father passed to him.

“I like to go fishing, take my grandkids fishing. I’ve got two grandsons, like to take them fishing,” Kennedy said. “I just want to preserve it.”

Note: the WVIC’s Jay Dick is the husband of WXPR station manager Jessie Dick.