Right now, loons are soaking up the sun on the coast of Florida waiting for the ice and snow to melt before returning to the Northwoods this summer to nest and breed.

Since 1993, Dr. Walter Piper has banded, weighed, and studied loons and their chicks on lakes across the Northwoods. He’s a professor of biology at Chapman University in Orange, California.

“Northern Wisconsin has become the most important place in the world for the scientific study of loon behavior and ecology,” said Piper. “We're learning more about loons in northern Wisconsin than in any other place. It's just an absolutely crucial study site.”

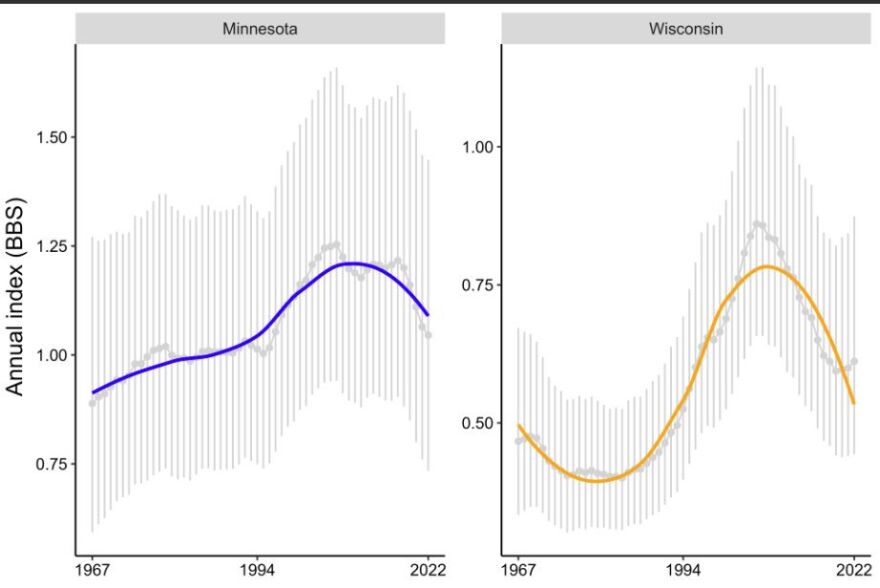

Over that time, he has watched the loon population thrive in the late 90s/early 2000s as well as sharply decline since that peak.

“There's been a decline in the adult loon population, and a real, very strong decrease in the rate of return, in particular, of young loons we put leg bands on,” said Piper. “We used to get close to half of all the birds that we banded as chicks come back, back in the 90s /the early 2000s, but now it's about 10 to 15% of all of those young birds coming back, so it's a really alarming, shocking decline.”

Decline in water clarity

Piper and his team will go out on lakes in July and August at night to scoop up the chicks and adults. They’ll put the bands on them and take their weight.

Along with the decline in numbers, Piper has seen a decline in chick weight.

“That is, chicks are just not as heavy as they used to be, and the obvious explanation for that is they're not getting as much food as they did before,” said Piper.

Piper worked with former UW Madison researcher Kevin Rose, now at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute of New York, and his student Max Glines to look at water clarity.

Looking at satellite data to estimate water clarity, they could see that in the years where the water was clearer in July, the chicks were heavier.

“In years when the water was not as clear, the chicks were not as heavy. There has been a steady loss of clarity, at least in our study, in lakes in Oneida and Vilas counties, and a little bit in Lincoln County as well,” said Piper. “That decline is certainly at least one important cause of the loss of the reduced survival rate of chicks and therefore the reduced survival rate of young adults.”

It's harder for loons to see through the water and find the fish that they need to feed their chicks.

Piper says it’s the “silver spoon effect”. The amount of food that a loon chick receives from its parents during its first five weeks of life affects its survival and breeding success throughout life. The chicks that don't eat as well are less likely to make it to adulthood and even if they do, they're less likely to reproduce.

What is causing the decline in water clarity, in particular on lakes with breeding loons, is still not certain.

Piper says it could be an increase in development along lakeshores and use of fertilizer washing into the lake and increasing vegetation, increased rainfall, increased sediment, wake boats churning up nutrients, or something they haven’t even thought of yet. Right now, they’re just hypotheses.

“We know that the water's clarity has gone down, and we need to pin down which of these factors might be at fault, and if so, we'd like to tell people, ‘Hey, this is what's happening, and let's see if we can turn this around, if we work together and decide we want to help loons out,’” said Piper.

Much like the loon population, Piper has watched funding for this loon research project decline over time.

Decline in funding

For more than a decade, Piper had been able to get federal funding through the National Science Foundation, but that’s been more challenging as grants have become more competitive.

Private foundations have helped fund the work including National Geographic, The National Loon Center in Minnesota, and the Walter Alexander Foundation in Stevens Point.

In the last couple of years, it’s transitioned to individuals supporting the work.

“In recent years, it's been almost exclusively funded by individuals just saying, ‘Hey, I love your blog. I think your work is important, and I want to support you,” said Piper.

But even that has become a struggle saying this year in particular has been difficult to get funds.

Pipers says their field work planned for northern Minnesota this year, where they’ve been doing similar work since 2021, is fully funded. But that’s not the case for the work he wants to continue in northern Wisconsin.

“It looks like we're going to have to scale back our efforts in Wisconsin. We'll keep it going. It's just too valuable to not do it, but it's going to be on a much lower level than what we're able to do in Minnesota this year,” said Piper.

Piper says it costs between $50,000-$60,000 to cover the costs of the field work in each state. It pays for things like stipends for field staff, lodging and travel, and needed equipment.

As Piper watches the decline in loon populations, he’s concerned if solutions aren’t found to reverse this trend, the Upper Midwest may eventually lose its loon population.

“It's an absolutely critical time to keep our work going, and I'm tearing my hair out to try to figure out how we can keep things going,” said Piper. “I'm going to work until I no longer can, to try to learn what’s harming loons in northern Wisconsin and I'd appreciate all the help I can get from other folks who, like me, love loons.”

Piper updates a blog to keep people up to date on his research at loonproject.org. That’s also where you’ll find information on how to support the project.