In the late 1990s, when Patrick Taylor moved back to his Merrill hometown, he bought a house on the water.

It was one of more than a hundred homes on a mill pond created by the old Ward paper mill dam.

“It was a great area for duck hunting,” Taylor said.

Other people on the water fished, swam, or canoed.

Then, Taylor learned the water was about to disappear.

“The day after we closed on the house, they announced the removal of the dam,” he said in an interview this week.

Twenty years later, the Prairie River meanders through Prairie Trails Park in what used to be the lakebed. The park features a trout stream, lush native grasses, and miles of walking trails.

But the park only got there after the DNR removed the century-old dam and mill pond on the site, a move that sparked protests, lawsuits, and even death threats. It was one a piece of an ongoing statewide project that’s made Wisconsin a national leader in dam removal.

In 1990s, International Paper, the Merrill dam’s owner, had left town.

No one was maintaining the dam, and it was a safety risk, said Bob Martini, who worked for the DNR at the time.

“The gates were the original wooden gates from 1905, when it was built. They were all warped, and they were really in bad shape,” Martini said as he looked at the old dam site next to the hulking former mill.

State law allowed for two options. The dam could be fixed, but that would cost more than a million dollars. No one wanted to pay it.

The only other option? Removal.

Martini was in charge of overseeing that removal process, which would drain the mill pond and let the Prairie River flow freely.

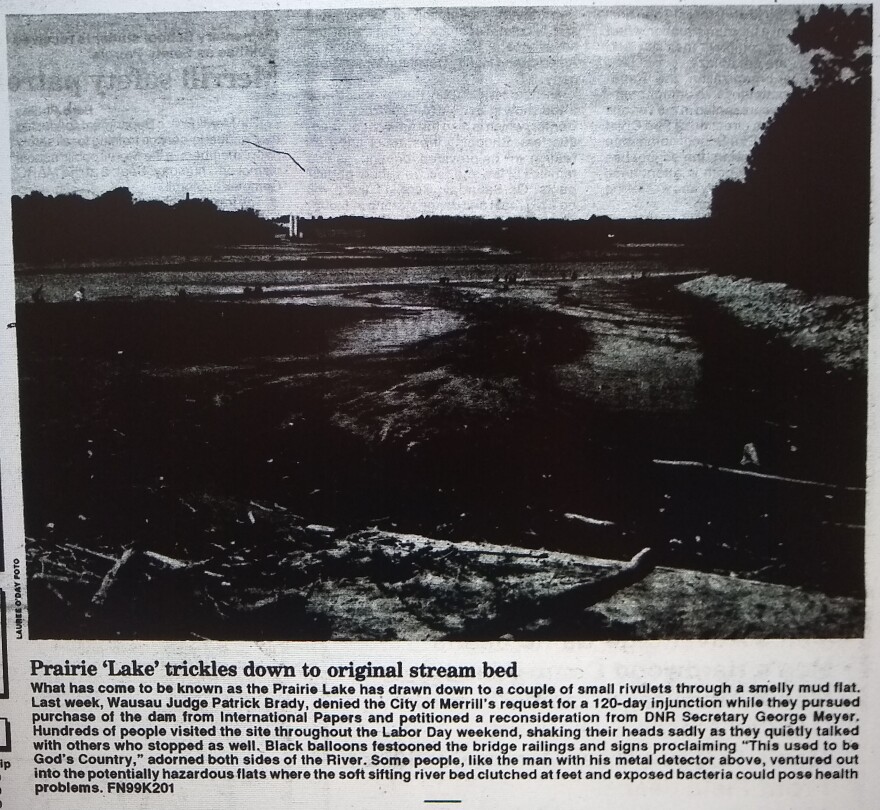

“Oh, [people] were pissed,” Martini said. “[They put] black balloons and black cray paper on the bridge, mourning the loss of the dam.”

Taylor helped lead a push to save the dam, and it started with a name change.

“From kind of a marketing perspective, who wants to save a pond? Why would you want to save a pond? We were like, ‘Look, when you refer to the mill pond, call it Prairie Lake.’ People are more likely to get behind saving a lake than they are saving a pond,” Taylor said.

As Martini and the DNR worked to remove the dam and return the Prairie River to a high-quality trout stream, he faced letters to the editor, nine lawsuits, and death threats.

But no one ever came up with the money to fix the dam, the lawsuits failed, and in a matter of days in September 1999, Prairie Lake was gone.

Within years, it was replaced by Prairie Trails Park.

“We used to climb the fence when it was the mill, and we used to fish, actually, where we’re talking right now, right in the corner over there,” said Dan Wendorf, pointing to the southwest corner of the park.

As Merrill’s Parks and Recreation Director for the last 17 years, Wendorf played a major role in the park’s development.

Trails, benches, a pavilion, and a natural habitat now occupy what was once the bottom of a manmade lake.

“This is probably quite a bit of what it looked like. We have some river bottom areas, we have some prairie grass areas. I know that I’m biased, but I think it’s beautiful here. We’re proud of it,” Wendorf said.

As the park was being planned, Wendorf said his committee wanted to keep local homeowners, who had lost their waterfront, in mind.

“We can’t do anything about bringing back lakefront, but, throughout the process of this, let’s try and give you beautiful park front,” he said.

Standing on a bridge over the Prairie River in the park, Martini calls the result a win for data, logic, and science over anger, fear, and emotion.

“It really is satisfying, especially when you have so much opposition,” he said. “Everybody can win. Everybody did win in this case. They were mad, but eventually, they won.”

Patrick Taylor might disagree.

He no longer lives in the house he bought in the late 1990s. He’s still in Merrill, but he’s never been to Prairie Trails Park.

“I’ve never walked through it, and I never will,” Taylor said. “It looks decent, but it’s not some place I’m going to spend my free time. Just bad memories.”

But removing the Ward Dam in Merrill was just one step in allowing the Prairie River to flow freely.

Before that project, Martini was instrumental in the removal of the Prairie Dells Dam upstream.

It was designed to produce hydroelectric power, but it never generated a single watt due to an engineering error.

“The engineer had misplaced a decimal point, and they couldn’t make it pay,” Martini said. “That dam sat there with no maintenance for a hundred years.”

Even through its infrastructure was failing, the DNR had to use dynamite to dislodge the dam in the 1990s. Now, a look down the steep walls of the Prairie Dells often reveals trout fishermen or kayakers below.

“After this one and Ward was taken out, the river ran free for the first time since the 1890s,” Martini said.

Prairie Dells and Ward are just two of the roughly 180 dam removals in Wisconsin over the last 50 years, according DNR State Dam Safety Engineer Tanya Lourigan.

The group American Rivers finds that, in the past century, Wisconsin trails only Pennsylvania in dam removals, which often improve fish habitat and enhance safety.

According to the National Inventory of Dams, Wisconsin's 1,000-plus dams have an average age of 81 years old.

Martini is retired now, but he says the state should keep looking at its dams.

“There’s lots of opportunities out there waiting to happen, because ice and gravity and just general deterioration are occurring on all of these structures,” he said.

Like in Merrill, removing some of them may cause hurt.

But Martini argues, in many cases, it’s just the right thing to do.

“We understand how much pain you have to go through to get to a good result at the end, but there are so many of those success stories in Wisconsin in dam removal, that it’s worth doing the work,” he said. “It’s worth going through the pain. We know that the result can be better.”

_