Steph Shaw starts the outboard motor of the small, flatbottomed boat, and takes off toward the middle of Katherine Lake in Hazelhurst.

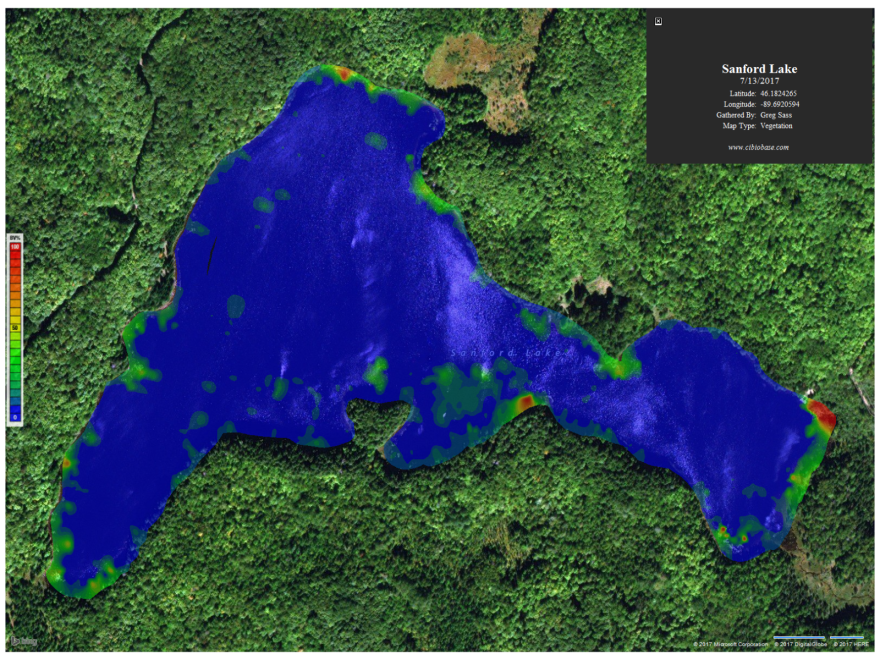

Dropping an anchor, Shaw uses a piece of simple equipment, called a Secchi disk, to measure water clarity. Other tools measure water temperature and oxygen levels. More sophisticated sonar equipment then provides a view of the vegetation cover underwater.

This work is being done by Shaw, a DNR fisheries researcher, and her team of technicians on about 30 lakes across northern Wisconsin.

It’s in pursuit of an answer to a mystery, the mystery of disappearing walleye.

“We’re seeing lakes that were stable in the past, had good natural recruitment, and they still do. They’re doing great and have really productive walleye populations. We’re also seeing populations that historically were stable. They were in good shape. Just maybe in recent decades, we’ve seen more declines. They’ve become less stable. There’s a lot of mystery. There’s a lot of potential issues,” Shaw explains.

Katherine Lake is one that has seen a precipitous decline in walleye populations. In the early 1990s, surveys found 9-10 age-zero walleye per acre. By the 2000s, it was 2-3 per acre. The latest survey, conducted in 2018, found just .01 walleye per acre.

Researchers have a few clues about what’s going on.

They believe larger lakes with more complex shoreline shapes suit walleye better, and walleye prefer cooler weather and cooler water.

But those are all things out of anyone’s control.

“As managers, we can’t actually manage that. We can’t manipulate that, essentially. So, if we’re looking for tools to be able to use to help promote or rehabilitate or support walleye populations, we need something that we can actually use or manipulate,” Shaw says. “We need tools.”

In-depth lake surveys like this one track things like downed trees in the water for habitat, human development along the shore, and lake bottom hardness, things humans can change.

What works to keep walleye reproducing?

Few are investigating those questions with the detail Shaw is.

“Yeah, this is probably one of the bigger projects for that kind of information in the state,” she says.

The end results, likely out in a few years, will offer hints that could revive stagnant walleye populations in some lakes.

But which lakes are the best candidates for trying to save?

After all, researchers from different study are confident climate change will severely hurt walleye.

“How will fish communities and fish populations, like walleye, change under a changing climate? What’s the walleye population’s [future]? How are they going to be in 50 years or 100 years?” says Craig Paukert, a researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey and the University of Missouri.

“Walleye fishing, at least in the northern part of Wisconsin, is probably not going to be as widespread as it is now.”

Paukert is leading a team looking ahead to the years 2050 and 2100.

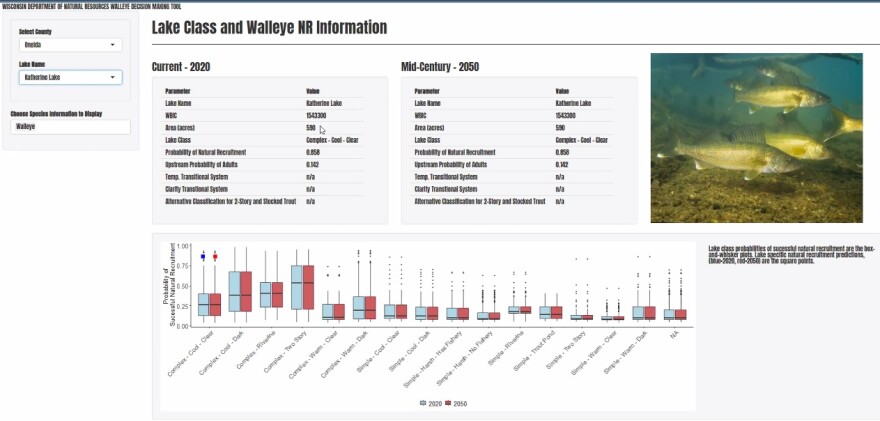

Colin Dassow is a postdoctoral member of the team who uses lake data and statistical modeling to predict how climate change will affect individual lakes.

“[We’re] looking across the landscape to figure out which lakes will have walleye in the future and which ones won’t,” Dassow says. “That is really useful for managers as they’re trying to think about, I have a limited amount of resources I can put into maintaining walleye. Which lakes am I going to get the most bang for my buck?”

Once the number-crunching is complete, managers will be able to see the likelihood of a given lake supporting walleye 30 years from now and 80 years from now.

“Lakes that are predicted to be resilient to the warming climate are lakes that are often in chains or part of a river or a flowage. They constantly have that cool water continuing to come into them,” Dassow says.

Both studies delve into the uncertain. Paukert and Dassow’s team seeks to predict the future. Steph Shaw’s work looks to figure out the mystery of disappearing walleye.

They also share this in common.

The answers to the future of Northwoods walleye are unlikely to come from one magic bullet. As Shaw puts it, there’s probably not one big gorilla in the room, one simple fix to the walleye woes.

“It would be wonderful if it was one gorilla that we could shuffle out of the room quick and get our walleye populations back on track,” she says. “But ecosystems are complicated. Everything influences everything else.”