On a pleasant morning last week, Sara Sommer and Chris Ester paddled to the deepest point of Luna Lake, a 64-acre lake in northern Forest County surrounded by National Forest.

Sommer and Ester, both Forest Service employees who work in the watershed program, unpacked what they brought on board. Sommer joked it looked like a “mad chemistry lab.”

Since 2013, the Forest Service has been collecting water samples here on Luna Lake. Some samples are just straight surface water. Others are sent through a filter rigged with a cordless drill. Chlorophyll tests require using air to push water through a special container. All samples will be sent to labs for precise testing on their chemistry.

It might seem strange, people who work for the forest so concerned about the water. But Sommer said there’s no gap between forestry and water issues.

“It’s all interconnected. Water and forest management and water quality, it’s all connected. I really think everything is connected,” she said.

In fact, more than half of America’s freshwater flows from forestland. About 60 million Americans rely on drinking water that originates on National Forests and Grasslands.

But there’s another connection, too, a connection between air quality and water quality, which is why Sommer and Ester are on this seepage lake.

“There’s no inlet or outlet, and the water it receives is from rain runoff,” Sommer explained. “There’s no groundwater input.”

Because no water flows through these lakes, they’re especially sensitive, collecting air pollution that falls to the ground as rain.

They reflect changes in air quality quite well, like in the National Forest’s Rainbow Lake Wilderness Area in Bayfield County, which has been sampled since the 1980s.

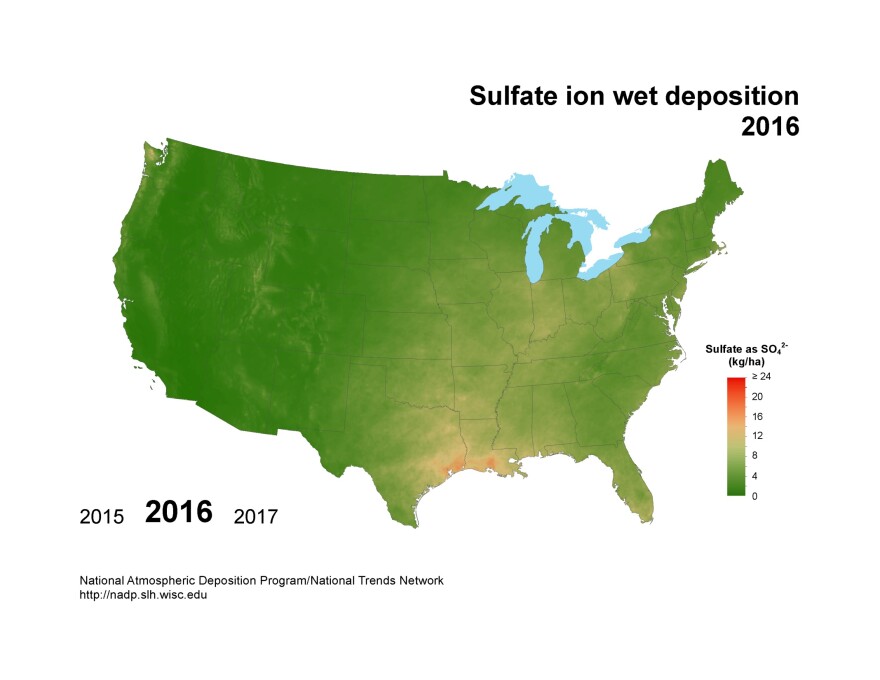

“From that data set, from 1984 to now, 2021, we’ve seen an increase in alkalinity. That is a measure of the lake’s ability to buffer acid,” Sommer said. “We’ve also seen a decrease in sulfur concentrations since that time frame.”

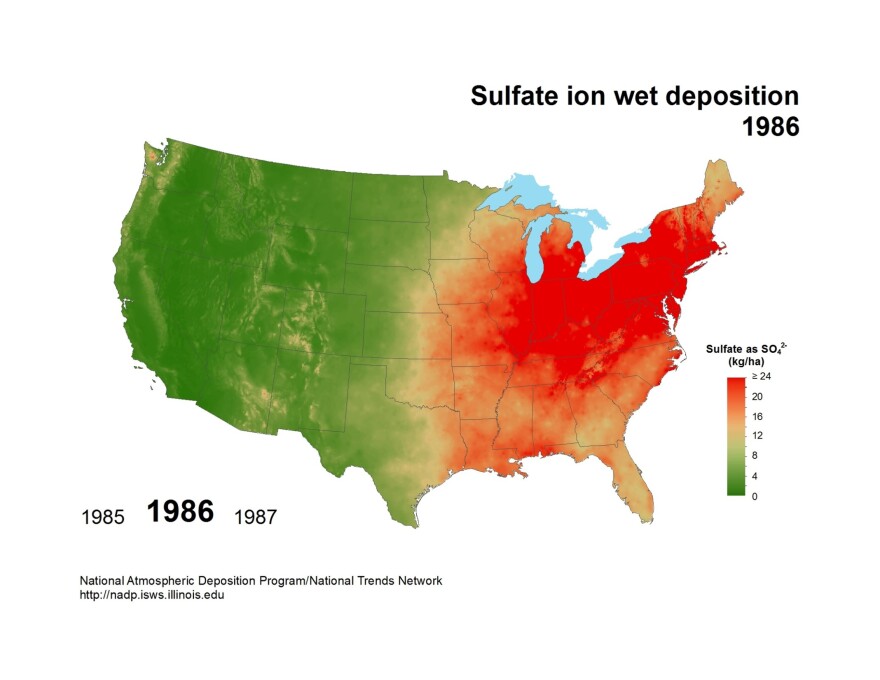

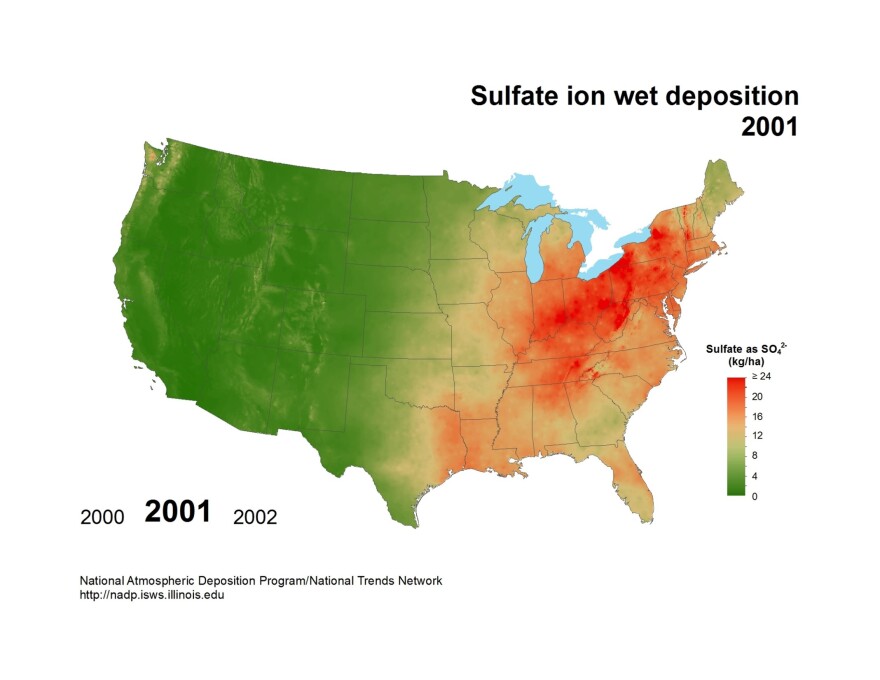

Sulfur emissions, which largely come from coal smokestacks, have plunged nationally since an amendment to the Clean Air Act in 1990.

Forest Service air resource specialist Trent Wickman studies air quality in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota.

He said lakes are among the best places to detect changes in air quality.

“In many cases, we can tie changes in chemistry that we see in the lakes to emission changes that we know have happened at industrial sources,” Wickman said.

This year, Wickman is also monitoring air quality issues that have nothing to do with industry. Instead, smoke from western, Canadian, and even Minnesotan wildfires has filled the sky.

“We haven’t had this level of smoke for many, many, many years. The level that we’ve seen this summer is somewhat unprecedented in recent history,” he said.

Wickman can’t say whether the effects of increased smoke will be visible in 2021 lake surveys.

If the trend keeps up, though, Sommer thinks indicators might be on the horizon.

“If we continue to have these fires like we do, maybe in ten years is when we’re going to see that, oh my goodness, there are some changes in the water quality from those impacts of fires,” she said.

Luna Lake is one of ten similar lakes across northern Wisconsin that the Forest Service has been sampling.

After next year’s tests, scientists will have data spanning 10 years, measuring pollution from both industry and fires.

That might be enough to draw some solid conclusions about the changing quality of the air we breathe.

“If we start seeing these trends, it’s something that we can speak to and have the proof that, hey, this is going on on the landscape,” Sommer said.