A WXPR investigation has found over a seven-year period in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the City of Rhinelander spread almost 400 tons of sewage sludge at the Rhinelander-Oneida County Airport.

Later, the city built two municipal water wells near the place where some of the sludge was spread. Last year, those wells were found to have high levels of PFAS, a chemical with known health risks.

Now, a nationally-recognized expert on PFAS and sludge says the contamination in the city’s water could have come from sludge spread three decades ago.

Roger Freund helped pick the spot for one of the two now-contaminated wells decades ago.

“Where we could get enough [water] for a decent well and water quality is what we were looking for,” Freund said.

Freund was Rhinelander’s water supervisor before retiring 16 years ago.

In 2007, a few years after he retired, Well 7 was completed, and in 2014, so was nearby Well 8. Together, they could provide 900 gallons per minute of water to the city.

But last year, both were shut down after testing revealed the wells were producing water with high levels of PFAS compounds. When ingested by humans, those so-called “forever chemicals” can lead to higher cholesterol, thyroid disease, and even cancer.

When Freund was exploring the future well site long ago, he didn’t consider testing for PFAS, because, like for many water operators, he hadn’t even heard of it at the time.

“That’s right,” he said. “But it is something now that, now that they know it’s there, it’s something you would test for.”

It’s impossible to say what pre-drilling PFAS testing would have revealed. But now, we know what might be a contributing factor to the PFAS contamination.

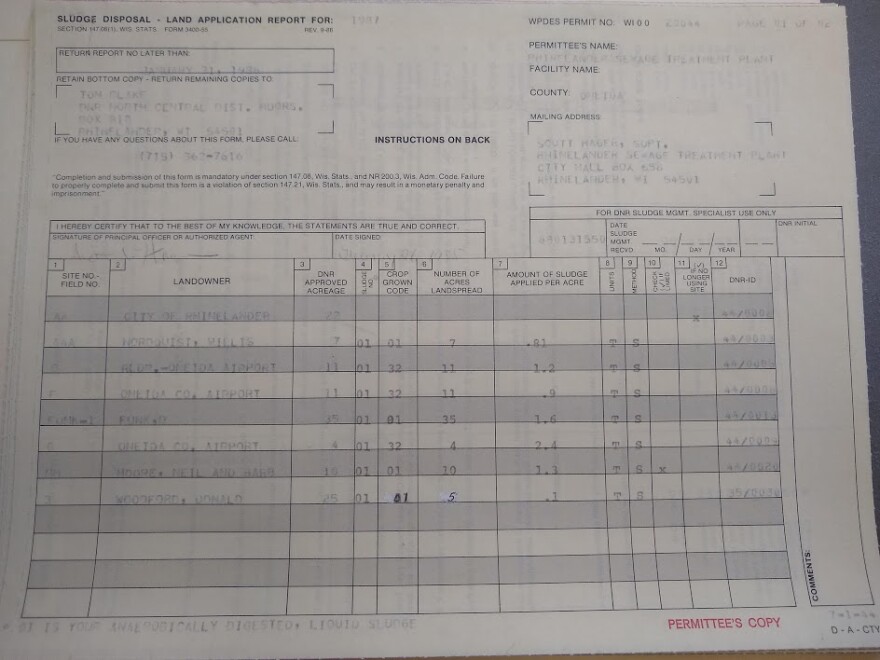

WXPR’s investigation revealed between 1987 and 1993, the City of Rhinelander spread or injected 390.11 tons of sewage sludge from its wastewater treatment plant at the airport. Sludge is the solid or liquid material left over when wastewater is purified and returned to waterways. It’s commonly, and legally, spread on agricultural fields and other land for disposal.

Images of the city's records of sludge spreading over the seven-year period, some of them faded, are below.

Retired airport director Joe Brauer remembers how the sludge-spreading system worked.

“I believe the truck that they used at the time was about 1,000 gallons. They did it probably two, maybe three times a day, four days out of the week,” Brauer said. “They did have injectors in it, when they worked, so it would inject the sludge into the ground.”

The sludge was spread all over the airport property, Brauer recalled, but some of it definitely was near where the wells were later built.

Could tons of sludge spread three decades ago account for PFAS contamination in the wells today?

It’s absolutely possible, said Dr. Rolf Halden, a professor at Arizona State University whose research includes PFAS in sludge. The topic is included in his new book, Environment.

Halden’s research has shown sewage sludge nearly always contains PFAS, since PFAS is in products we use every day and their waste.

“They get into the wastewater treatment plant. They accumulate in sludge,” he said. “What does that sludge look like? Well, it looks like exactly what we’re doing, and since we’re using these chemicals everywhere, the sludge everywhere also contains this type of chemistry.”

PFAS, including when spread as sludge, often doesn’t go far or break down.

“They are around. They don’t go away. You can park them for 100 years. We call them the ‘eternal pollutant,’ so they will be here long after we are gone,” Halden said.

A WXPR open records request showed, in the lead-up to building Wells 7 and 8, the city didn't mention the sludge spreading it had done years before as a potential contamination source.

You can view these documents through the links at the bottom of this page.

State law prohibits well drilling within 1,000 feet of a sludge site, but that only applies to current or future spreading sites, the DNR said.

That spreading ended in 1993, according to Brauer, because the sludge was attracting worms, which were attracting birds, which were a hazard to nearby airplanes.

Even though sludge appears to be a potential source of Rhinelander’s PFAS problems, Dr. Halden can’t rule out the possible source identified first.

In December, the DNR sent the airport a letter labeling it a “responsible party” for the contamination and referencing to fire-fighting foam stored near the main terminal.

“In terms of proximity to the wells and in terms of unknown storage and potentially past use of these fire-fighting foams, they would be the most likely, or a likely, close-by source,” said Chris Saari, the DNR's Northern Region Program Manager for the Remediation and Redevelopment Program, at the time.

These foams are a known source of PFAS, but airports are required to store them in case of emergencies.

In Rhinelander, they’ve never been used in an active situation. A few gallons are sprayed into a bucket for testing each year, said Airport Director Matthew Leitner.

“We don’t use it regularly. We use it extremely sparingly. It’s not something that we play with. It’s not something that we would ever play with,” he said.

Leitner was even more confused his foam was implicated, since it’s stored a half-mile away, in a spot where groundwater runs away from the wells.

“When they came back and said, ‘Well, we’ve identified you as a responsible party,’ yeah, it was surprising,” he said.

After learning about the sludge-spreading records, Leitner called the DNR’s original move a “hasty conclusion.” But Leitner’s DNR-mandated environmental investigation continues, a significant unbudgeted expense for the airport.

For his part, Dr. Halden can’t rule out the foam because, he said, water can move and carry chemicals below the surface in unpredictable ways.

Former airport director Joe Brauer thinks the DNR got it backward, that the nearly 400 tons of sludge spread in the late 80’s and early 90’s should be the agency’s first target for investigation.

“Hey, maybe that culprit could be that. I think that the DNR might be better off looking at that direction versus, basically, looking at the foam and saying basically the airport is guilty until proven innocent,” Brauer said.

On Monday, Saari, the DNR regulator, said the newly-discovered sludge records are “something that we would evaluate.”

First, though, “we need to see the results of the site investigation,” the work done by the environmental consultant the DNR required the airport to hire after the responsible-party declaration.

Rhinelander Mayor Chris Frederickson declined to comment for this story, besides saying he’s following the situation closely.

Documents omitting mention of wastewater sludge spreading in the vicinity of Well 7 include page 16 of this report, page 3 of this report, and page 20 of this report. Documents omitting mention of the same near the Well 8 site include page 50 of this report.

City of Rhinelander wastewater treatment plant sludge spreading records for the years 1987 to 1993 are below.